Microaggressions Impact Student Learning and Classroom Dynamic

Microaggressions come in various forms and can amass into a detrimental impact

Microaggressions have become troublingly normalized in modern society. Schools, as microcosms of society, are not exempt from this issue; underrepresented students battle not only microaggressions, but also the implications they cause to a learning environment.

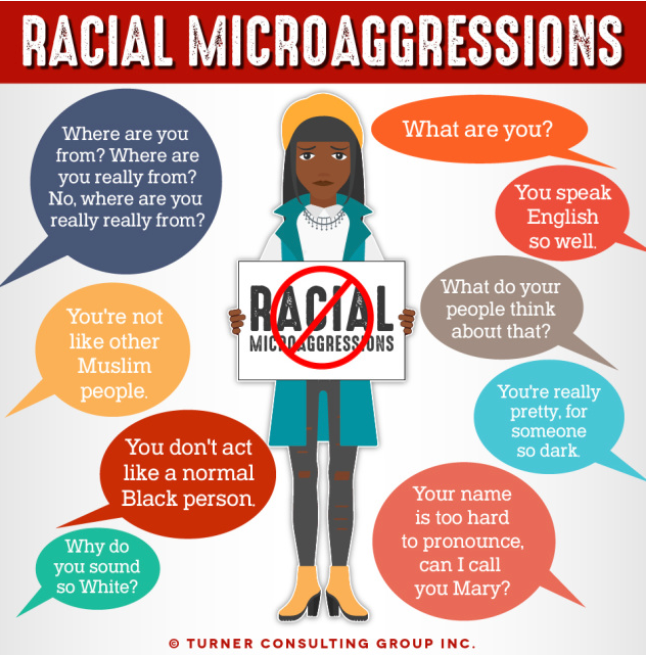

The Merriam-Webster defines a microaggression as a comment or action that subtly expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group, such as a racial minority.

While junior Jenny Duan accepts this definition, she recognizes the need for further details.

“Microaggressions can either be implicit or explicit,” Duan said. “Oftentimes, the aggressor doesn’t realize that what they’re saying is hurtful and is usually based on stereotypes or false perceptions of people.”

Duan, a Chinese American daughter of immigrant parents, recognizes the harm that microaggressions can cause. She agrees that microaggressions have become alarmingly normalized in everyday life, especially in colloquial conversations.

Senior Aliyah Ramirez contends that microaggressions are especially prevalent in the classroom. She has personally experienced microaggressions unjustly correlating her Latin American heritage with her intelligence. These comments have degraded Ramirez’s confidence in her academic abilities, impacting her learning.

“I think [these microaggressions] definitely make you question your intelligence,” Ramirez said. “I know that I’ve had to work extra hard just to prove my intelligence when it’s being insulted because of my ethnicity or my skin color.”

Senior Amen Zelalem has also faced microaggressions in the classroom which impacted her learning. In her case, the microaggression was committed by a teacher who used a derogatory Asian slur. While the action did not personally affect Zelalem, who is of Ethiopian descent, she still felt discomfort in the instance.

For the rest of the class, Zelalem’s attention was solely focused on the microaggression, distracting her from the day’s lesson. She was torn as to whether she should speak up about the microaggression or remain silent since it was not directed towards her culture.

“It’s hard to be in a class where the teacher is supposed to be teaching you, but you feel like you need to teach the teacher,” Zelalem said. “It feels like too much to be trying to make both the students and teachers less ignorant about their microaggressions on a daily basis.”

The issue with microaggressions is how subtle they are; they usually fly under the radar except for the people that they affect. Microaggressions affecting students in schools are especially problematic as children are so vulnerable. Continually dealing with microaggressions in a school environment negatively affects student learning, especially for underrepresented communities.

Diving deeper into this issue, Mia Simmons embarked on a research journey to explore the impact of racial microaggressions on students. Simmons, a recent graduate of the class of 2020, culminated her high school career with this project. Her main impetus for this journey was recognizing the need for a more inclusive race and culture-based education.

“I wanted to have sufficient research to be able to educate people on microaggressions,” Simmons said. “I think this is a problem that some students have to face while others have the privilege of not even knowing what it is.”

Simmons’s research journey solidified the notion that microaggressions do impact student learning. In particular, she cited a 2007 study by Columbia University about the implications of microaggressions on student learning.

“Microaggressions are detrimental to persons of color because they impair performance in a multitude of settings by sapping the psychical and spiritual energy of recipients and by creating inequities… Experience with microaggressions results in a negative racial climate and emotions of self-doubt, frustration, and isolation on the part of victims,” according to the study. “These feelings of self doubt can make it difficult for a student to feel like they belong in a class,” Simmons added.

These adverse effects of microaggressions will continue to affect students unless teachers and students have adequate racial literacy training, according to Simmons. Expecting students of color to be responsible for handling microaggressions adds unnecessary—and quite frankly unfair—stress.

“I think teachers and school administrators have a lot of responsibility,” Simmons said. “The culture of how students treat each other is set by teachers. If teachers have sufficient training to set an environment where microaggressions are unacceptable, that’s a big step to preventing the harmful impacts microaggressions can cause.”

Simmons stresses that teachers and administrators have a duty to incorporate racial literacy education to foster an inclusive learning environment. Conversely, students have a duty to engage with that education to develop their racial literacy. The burden for racial literacy does not lie solely on teachers; students must do their part as well.

In the end, it really does come down to education for both students and teachers. Developing a racial literacy education is crucial to handling microaggressions and the harm they cause to student learning.