Consent Education Empowers Today’s Youth

Consent education starts at a young age, with teaching children how to respect each other’s boundaries.

“‘What were you wearing? Were you drinking? Were you dancing? Were you smiling too much?’ Those are the questions police asked me before they told me, ‘We’re sorry for what happened to you, but there’s nothing we can do.’”

Author and business expert Jessica Long was just a young woman when she was drugged and sexually assaulted. Long told her story to thousands of people as her outfit was featured in the What Were You Wearing? exhibit, recounting the questions police asked and the outfit she was wearing that night: a blue dress, black tights, and boots.

Jessica Long is just one example.

Oftentimes, cases like Jessica’s and the public’s perception of them become an issue of understanding consent.

Defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as “compliance in or approval of what is done or proposed by another”, consent can apply to children, teenagers, and adults in a multitude of situations.

In the most basic sense, the idea of consent often arises with kids at a very young age.

Whether it’s a grandmother asking her grandchild if it’s ok to give them a hug, or a student asking their peers if they want to play a game, children are introduced to the concept of consent in their early years by parents and teachers. Despite this, the word “consent” is rarely ever used with young children.

“I don’t think I’ve ever used the word ‘consent’ with a three-year old before,” educator Gideon Kahn states in an article by Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Instead, children are taught about asking for permission and encouraged to stand up for themselves, particularly when they are feeling uncomfortable. More often than not, the goal is not to establish what exactly consent is with children, but rather to encourage them to use their voices and express their feelings to lay the groundwork for healthy communication and strong relationships.

Later down the road, consent becomes a more solidified concept for middle and high schoolers, the goal shifting to establishing a clear understanding of consent in academics, social interactions, and relationships.

Using tools such as the widely known tea video, connecting getting consent to offering someone a cup of tea, and the F.R.I.E.S (freely given, reversible, informed, enthusiastic, and specific) acronym, consent education in schools strives to teach impressionable young adults how to respect others’ boundaries. This is frequently woven into schools’ sexual education curriculum as the idea of consent is often associated with sexual activity.

Consent awareness in media and schools, however, was not always a popular topic of discussion.

Oregon specifically did not pass any legislation mandating consent education until 2015, when as part of a nationwide movement including 36 states, it adopted a version of Erin’s Law.

So why has consent become such a major topic in recent years?

The development of the #MeToo movement, played a large role in the growing attention to consent education.

Founded in 2006 by survivor and activist Tarana Burke, the ‘Me Too’ movement was meant to be resource for those affected by abuse, providing support, pathways to healing, a community to lean on, and working to disrupt sexual violence wherever it was happening.

It wasn’t until 2017 when the #MeToo hashtag went viral that the world began to pay attention to the extent of the issue of sexual violence.

When actress Alyssa Milano called out director Harvey Weisntein using her #MeToo platform, the hashtag began to garner attention, calling out issues of sexual assault in the workplace, in homes, and in schools.

#MeTooK12, a hashtag stemming from the original movement, called attention to sexual assault and harassment issues in schools specifically, bringing awareness to the growing number of children and young adults experiencing sexual violence.

This particular hashtag call

ed into attention an insufficient sex education program implemented throughout schools in the United States. Citing the hashtag as evidence, many large news platforms and education resources such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Education Week, argued important topics such as dating violence and consent could no longer be left untaught until college.

More recently in the media, influencers on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok have once again brought consent education into focus.

One such influencer, Andrew Tate, was among the most popular influencers on TikTok in 2022 with his videos describing his violent approach to ‘handling’ women garnering almost 12 billion views, and leaving a negative impression on his mainly teenage audience.

“I think, especially through TikTok, that [Andrew Tate] is one of the biggest concerns in the media,” said senior Noah Deklotz. “He’s transforming a whole generation of younger guys and teaching them to hate women and teaching homophobia and sending a lot of those messages. He’s one of those people that needs to be off media.”

In addition to the influence of the media and the #MeToo movement, recent revelations regarding the magnitude of sexual violence in the United States also make consent education especially important as a measure to curb sexual violence.

According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), every 68 seconds, another American is sexually assaulted. One in every six women and one in every 33 men have experienced an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime.

In one five-year period, Child Protective Services found evidence to suggest 63,000 children each year were victims of sexual abuse. 66 percent of those children were ages 12 – 17.

And perhaps most shocking of all, out of every 1,000 sexual assaults, 975 perpetrators will walk free.

It is important for young adults to be aware of this reality in the United States. Consent education has grown in order to encourage those children and teenagers to use their voices, to understand when they are in danger, and to work to prevent abuse wherever it may occur.

When asked why they thought it was important to teach consent, individuals in the Jesuit community had various answers, but all came to the same conclusion: teenagers need to understand consent.

“We are really protected at school with a bunch of people protecting us and teachers we can trust. In the real world, it can be harder to find people you can trust,” junior Melanie Rosales said. “Being as educated as possible going into your adult life is really important.”

Activities Director and Varsity Lacrosse Coach Lauren Blumhardt leads her lacrosse team through one practice each year dedicated solely to understanding consent.

“Women can tend to hide their voices so as to never disappoint someone. If we talk about the importance of consent, we can get better at respecting the choices of others and finding strength in our voices,” said Blumhardt

At Jesuit High School, consent education takes place sophomore year during health class.

“We talk about various types of consent throughout the year so by the start of the sexuality unit in the spring, the students feel comfortable having real conversations,” Jesuit health teacher Liz Kaempf said.

In connection with the school’s Catholic faith, sexual education is abstinence-based. However, abstinence-based education does not disregard or lessen the importance of teaching high schoolers consent.

“Consent would fall into the dignity of the human person,” said Jesuit Theology teacher Greg Allen. “The Church is always going to say that when sexual activity is morally justified, let’s say John and Jane are married, there still has to be consent because, without it, there is no respect for human dignity.”

As a Catholic college preparatory institution, Jesuit takes a comprehensive approach to consent education, focused around empowerment; that is, understanding your own and others’ boundaries and being able to respect and stand up for them.

Mrs. Kaempf conducts an anonymous survey of her classes asking what they know about consent, why they feel it is important, and what concerns they have about understanding consent.

In one such survey from a 2021 health class, students responded starkly:

“As a young woman in our country, I have thought a lot about consent, and it’s something that makes me very nervous. According to recent studies, one in three or four women is sexually assaulted in her lifetime. This means she did not give her consent to have sex, but her partner forced it on her. This is truly my worst nightmare. I’ve been raised to keep a wary eye out for men who could want to hurt me, and quite honestly they are everywhere.”

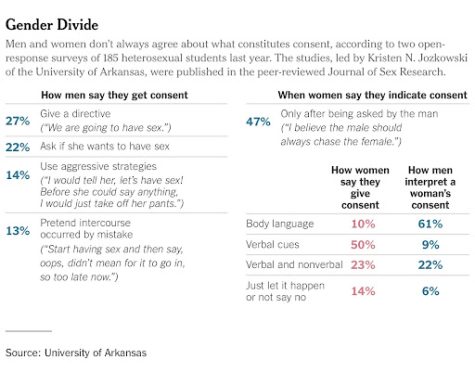

Other concerns from female students included “not realizing the other person isn’t consenting because usually the guy waits for the girl’s go ahead” or that someone might, “slip me a date rape drug”, “assume certain clothing, makeup, or action is consent”, or even, “guilt trip me into doing something I don’t want to do.”

Young men in the class also volunteered their concerns about consent as a teenager.

“I don’t want to make someone uncomfortable,” said one student.

“My main concern would be accidentally misinterpreting something and hurting someone,” said another.

Based in part on the students’ responses, health teachers highlight several topics in particular: verbal versus nonverbal consent, the impact of substances on consent, and bystander intervention.

In addition to health classes, advocates for increased education about consent integrate the topic into clubs, sports, and more.

“The more that we can inform our young [people], the more they are empowered to make decisions that best benefit them,” Blumhardt said. “Consent is key in all areas of life, it shows respect for oneself and the people around them. Talking about consent with my players lets them know that their voice is just as important on the field as it is off.”

Despite Jesuit’s comprehensive approach to educating students, there are some changes advocates for consent education feel should be made.

For example, health teacher Liz Kaempf would like to see more consistency in consent education at Jesuit.

“I believe consent should be taught in some capacity throughout all four years at Jesuit,” Mrs. Kaempf said, “It is especially important for our seniors leaving Jesuit to understand consent and the importance of it. It’s something that needs to be revisited.”

One student suggested a refresher course similar to the financial literacy course all students are required to complete over the summer prior to their senior year.

“It could, essentially, be like a real life crash course version of what we learn sophomore year,” the student said.

Similarly, Ms. Blumhardt would like to see consent addressed more often outside of sexual context.

“Consent is just not a one-topic issue,” Blumhardt said. “You need consent in all aspects of life.”