In 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), HAL 9000 tries to kill the astronauts aboard the ship it was assisting. In The Terminator (1984), a cyborg is sent from 45 years in the future to kill a woman. In The Matrix (1999), intelligence machines turn against humanity and create an alternate reality.

Throughout the years, artificial intelligence and the development of technology has long been depicted as a danger to society when capable of wielding too much power.

As artificial intelligence is gaining international traction and development, many schools and institutions around the world are introducing new policies regulating the ethical and harmless use of AI.

So what is the best way to regulate AI in schools?

At Jesuit, there is one mention of AI in the Student Handbook. In section 3.16, the Academic Integrity section, they state: “Using AI to generate content submitted by a student without explicit permission from the teacher to do so” (16). This is the only school-wide enforced policy about AI.

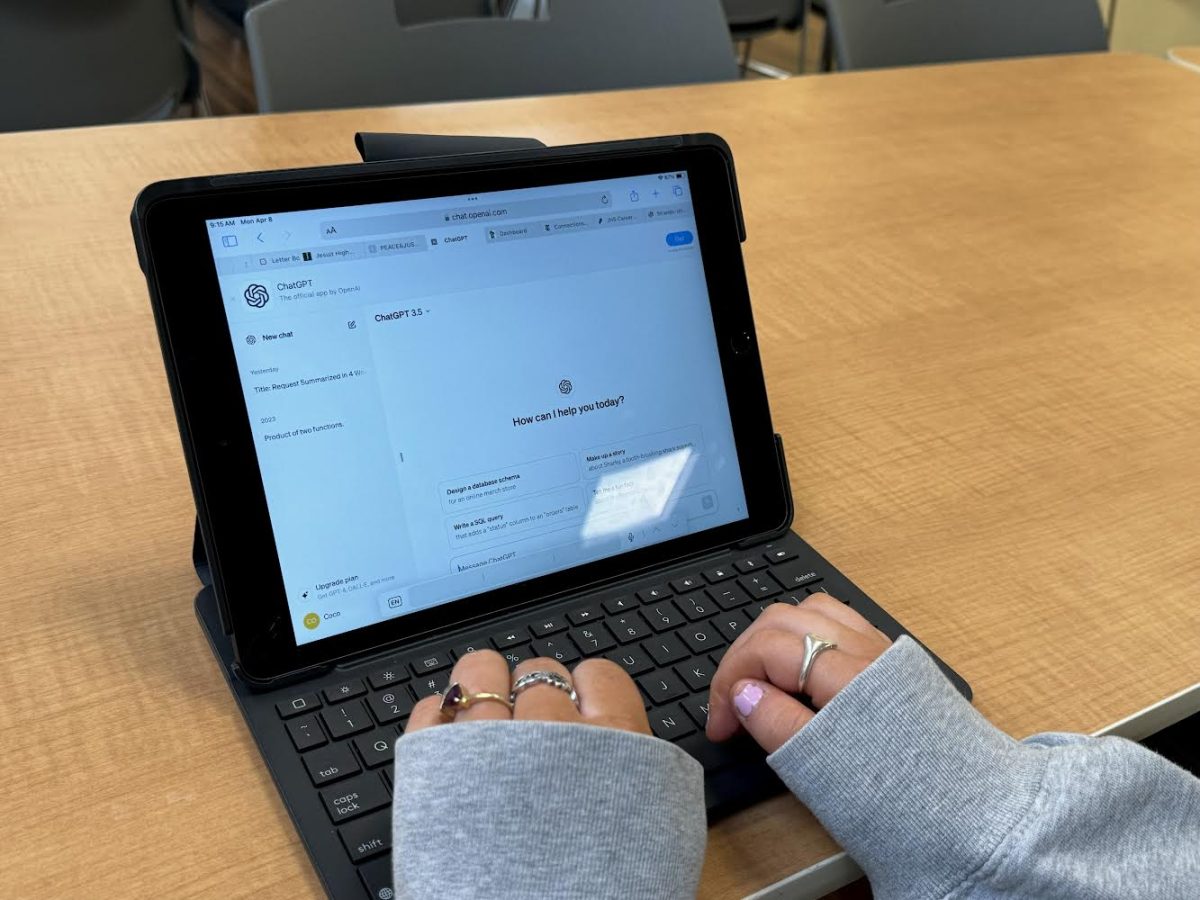

Currently, the majority of Jesuit students are using AI at some capacity–whether it be ChatGPT, Flint AI, or a simple Google search that automatically sends you to AI overview results.

At Jesuit, AI is expected to be an assistive tool rather than a tool that will generate content for students. Throughout the school, different classrooms and subjects have a multitude of AI policies. STEM classes have policies that differ greatly from English classes or Art classes.

Aya Brigham, senior at Jesuit, said that her STEM classes allow the use of AI for homework help.

“I think AI has really helped me. It’s nice to have something that can answer all of your questions, especially when you’re at home, doing your homework, without a teacher around.”

She said that specific subject regulation is better, arguing that in Math and Science, she believes that AI can help you grow as a learner, whereas it will inhibit that process in Humanities related subjects.

Senior Alexa Schreiber, an art student, believes that AI should also be regulated through subject-specific policies: “[F]or Math, we can use it to help us learn, as a learning tool when we can’t contact our teacher, but for Art, we’re doing our learning in class”.

The AI policy in some English classes is based on red, yellow, and green light assignments. If a teacher specified that an assignment is red, no AI use would be allowed for completion of the assignment. If green, AI is encouraged to be used.

Mariam Jawed, senior, believes that while this policy can be useful, AI inhibits the learning of language and literature, and there is little to no room for it in English classes.

“English is mostly learning, and comprehension, and AI coming up with ideas for essays and analysis and words to use in your essay don’t really help you learn and they take away the creative aspects of English.”

Subject-specific regulation could create confusion for students as to which classes allow AI use, and to what extent. However, it may be beneficial for certain subjects to use AI and others to not, so as to teach students the responsible and ethical uses of AI.

Science and Math-oriented classes may have a more justifiable purpose for AI. It can help students with homework by walking them through step-by-step problems or concepts. It can generate practice problems that students can use for extra studying.

In English classes, an integral part of learning is the process of analyzing and interpreting texts or language. Art classes are similar, in that they require students to be creative and original in their work. These subjects depend on the creativity of students and their ability to perceive the world around them, something AI is incapable of.

So what will the future of AI in education look like? Unregulated, it will redefine learning, and potentially end it. Regulated, it could be used to refine STEM subjects and careers and further the development of those fields.

AI wasn’t used to write this article; will there ever be a time where it will?

Opinions published on Jesuitnews.com represent the beliefs of the writer(s) and don’t necessarily reflect those of Jesuit Media, Jesuitnews.com, The Jesuit Chronicle, or Jesuit High School.